Nuclear power is back in vogue. Government targets on net zero along with a desire for greater energy security after Russia’s invasion of Ukraine have led to a surge in new projects around the world in recent years.

But increasing nuclear energy capacity is not easy. Projects across the globe have been fraught with delays and budget overruns, with the Financial Times revealing last week that France is pressing the UK to help fill budget shortfalls at the Hinkley Point C project in England, being built by EDF.

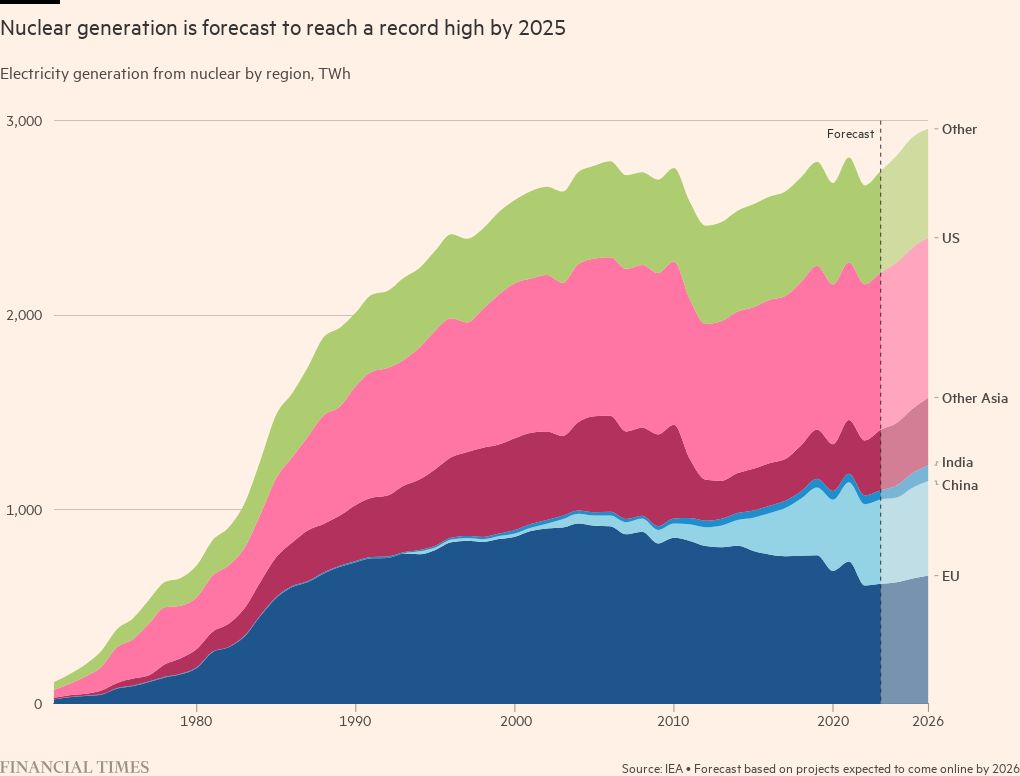

The International Energy Agency (IEA) says nuclear projects starting between 2010 and 2020 are on average three years late, even as it forecasts nuclear power generation will hit a record high next year and will need to more than double by 2050.

Technical issues, shortages of qualified staff, supply-chain disruptions, strict regulation and voter pushback are the key factors developers and governments are grappling with.

Technical and construction issues

When EDF confirmed last week that the Hinkley Point C nuclear plant in Somerset, England would be delayed by at least a further two years to 2029 at the earliest, it blamed technical problems: the complexity of installing electromechanical systems and intricate piping.

EDF is hoping that building multiple projects at scale will help it overcome these technical issues, enabling it to learn by doing and resolve problems with design.

In the US, Georgia Power is scheduled to complete work within weeks on the second of two gigantic new nuclear reactors that are at the vanguard of US plans to rebuild its nuclear energy industry.

But the expansion of Plant Vogtle is seven years late and has cost more than double the original price tag of $14bn due to a series of construction problems, highlighting the complexity of nuclear megaprojects.

Government subsidies and geopolitics

These complexities, high costs and long build times — as well as risks of nuclear accidents — make nuclear power a daunting prospect for many investors. As a result, the sector is heavily subsidised by governments. Many reactor suppliers for large-scale projects are state-owned, working alongside the private sector to build the full plant.

But countries also have a limit on how much they are willing to spend. EDF, now fully owned by the French state, will limit its stake in its next planned UK plant, Sizewell C, to 20 per cent.

Many of the new reactors being built across the globe are being supplied by Russia and China, which brings them geopolitical bargaining power. Chinese and Russian reactors account for 70 per cent of those currently under construction, the IEA said.

Russia’s Rosatom is supplying several new reactors for India’s Kudankulam nuclear power plant. India plans to triple its nuclear power by 2031 with 19 new reactors. But in the past the country has struggled to scale up its nuclear capacity, with projects beset by delays while foreign companies have been put off by strict liability rules.

Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s government, which says it wants India to become the world’s third-largest atomic energy producer after the US and France, has sought to increase the financing available for projects and encourage investment in small modular reactors.

Some countries are facing voter pushback on nuclear power. In Japan, local political resistance to reopening nuclear reactors remains strong following the Fukushima disaster in 2011. The topic is also a political lightning rod in Australia after nuclear power was in effect outlawed in 1998 at a time of significant public opposition to uranium mining and nuclear testing.

Uranium supply chain complications

Yet Australia is heavily involved in the nuclear supply chain as a major producer of uranium ore, which is essential to nuclear power generation.

Kazakhstan was the world’s largest miner of uranium in 2022, followed by Canada, Namibia and Australia, according to World Nuclear Association data. Political instability and production difficulties in Kazakhstan have pushed up prices and benefited rival producers in Australia in recent months.

Uranium enrichment supply chains are also fraught. Almost half the world’s commercial enrichment capacity is in Russia.

Countries such as the US and UK are now trying to break Russia’s dominance. In January, the British government said it would invest £300mn to develop UK production of Haleu, or high-assay low-enriched uranium, used in small modular reactors.

Global talent wars

Stop-start investment in new nuclear plants in many countries has made it harder for the industry to develop experienced staff as well as iron out technical problems.

Finding engineers with the right skills is a particular problem. The closure of Japan’s reactors following the Fukushima disaster led to a slowdown in new engineers joining industrial conglomerates such as Mitsubishi Heavy Industries and Hitachi.

France has said it needs 100,000 extra people in the sector, from welders to electricians, by 2030 and similar staffing issues have been noted elsewhere, including in the UK. “There’s a fight for talent in the whole energy sector,” said Linda Pålsson, head of energy at consultancy AFRY.

Future solutions

Governments continue to try to entice the private sector to help. The US and Sweden have deployed state guarantees on developers’ financing to incentivise private sector support.

Several private companies are involved in the race to develop new, smaller reactors that proponents hope can be built faster and cheaper than the large-scale nuclear projects under construction today. These range from the UK’s Rolls-Royce to US-based Westinghouse, owned by Canadian investment giant Brookfield alongside uranium supplier Cameco.

Private investors, including Bill Gates and Open AI chief executive Sam Altman, are backing start-ups developing small modular reactors, the first of a new generation of nuclear reactors.

Other countries are pursuing the political route. France has sought to position itself as one of the western world’s nuclear powers and has taken a lead in negotiating concessions for the sector within the EU.

Successes have included getting more favourable treatment for atomic power in reforms aimed at attracting investment and winning carve-outs in an electricity reform to direct more state subsidies to existing nuclear power plants. Paris is also hoping to convince the European Investment Bank to finance the nuclear sector.

Ultimately, efforts to make the case for more nuclear power come at a time of huge change in the energy sector, with investment being poured into competing technologies such as renewables, hydrogen and batteries.

Budget blowouts and delays do little to reassure potential investors that nuclear is a sensible bet. For nuclear’s revival to endure, it will have to get both faster and cheaper.

Additional reporting by Sarah White, Edward White, Benjamin Parkin, Leo Lewis, Jamie Smyth, Song Jung-a, Nic Fildes, Raphael Minder and Chloe Cornish